-James Chai, November 29, 2017.

COMMENT | I am most embarrassed when my friends ask me what I am doing. Because my answers will always either be “studying” or “working”. To the dismay of my lack of leisure, one friend once said to me: “Because you’re a Chinese, right?” I was baffled; my reply of “yes” was forced.

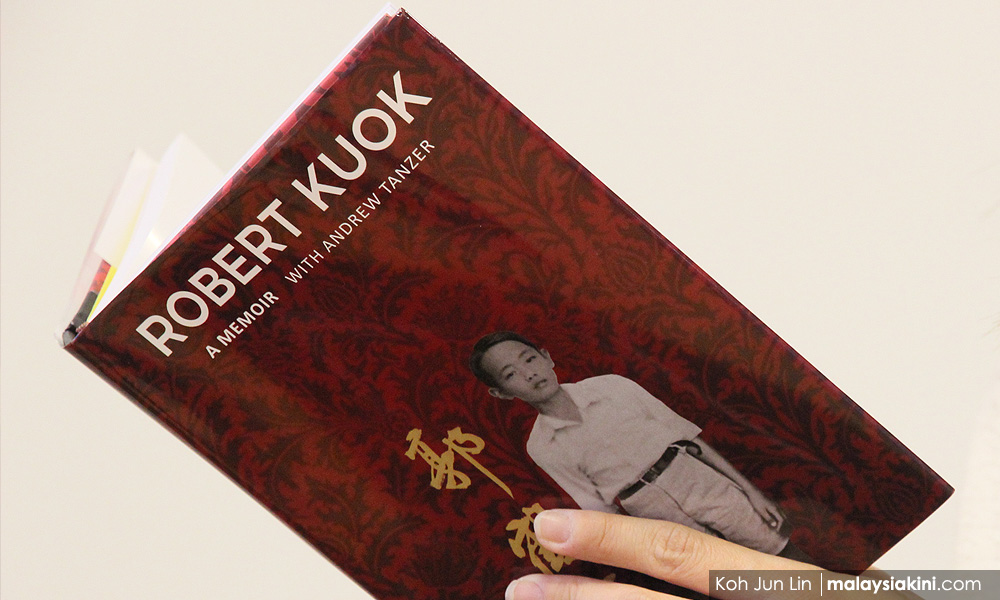

While he had said it as a throwaway remark, the stereotype of the “hardworking Chinese” seems long accepted. In billionaire entrepreneur Robert Kuok’s upcoming memoir, he called the overseas Chinese ‘the most amazing economic ants on earth’.

Robert Kuok is one of the remaining sages of our country, and his insights are surely representative of a worldview that is much broader than ours.

So, it is timely to ask the question: why do the Chinese work so hard?

Kuok (photo) suggested a mixture of two things: one, genetics; two, culture.

Kuok (photo) suggested a mixture of two things: one, genetics; two, culture.

On genetics, he attributed the Chinese hardworking attitude to ‘being blessed with some of the best entrepreneurial genes in the world’. In other words, the Chinese are simply “born” hardworking.

This is a strong assertion that is hard to prove, since scientific research had shown that any qualitative assumptions about race are at best non-generalisable. Gone are the days where social Darwinism had mainstream prominence, not least because of the destructive political and social ramifications it had brought.

This might simply represent his own subjective opinions, to which he would find an ally in the young Dr Mahathir Mohamad when he first published “The Malay Dilemma”.

Thus, on Chinese being “born” hardworking, it is merely Kuok’s opinion, and nothing more.

Cultural legacies

But there may be some truth in saying the Chinese were culturally “taught” to be hardworking. Malcolm Gladwell’s seminal book, “Outliers”, argues that cultural legacies matter. That means there are some things that are taught by Chinese families to their children, which were passed on from generation to generation, that made them value hard work more.

Kuok said that even for the most uneducated Chinese, family education, upbringing, and social environment have inserted ‘hard work’ into the cultural bone marrows of the Chinese. Kuok added that if an overseas Chinese was penniless, he will do everything in his power to get his first seed capital.

“No food without blood and sweat” is a famous Chinese saying. Martin Yang, the author of “A Chinese Village”, sampled a speech from a typical Chinese family:

“Listen children, there is nothing in this world that can be won easily. A piece of bread must be earned by one day’s sweat… The desire for better food, better dress, a good time, or the easy way will lead but to ruin of our family.”

This has a striking resemblance to what my father said on the dining table, and what my teachers in Chinese primary school had taught me about the value of a grain of rice. Every grain of rice is a result of blood and sweat, so we must recognise this in every bite, without ever forgetting the fundamental philosophy of hard work.

This has a striking resemblance to what my father said on the dining table, and what my teachers in Chinese primary school had taught me about the value of a grain of rice. Every grain of rice is a result of blood and sweat, so we must recognise this in every bite, without ever forgetting the fundamental philosophy of hard work.

The wasted grain of rice

Myths then started developing on wasted grains of rice. We were told that our future spouses will have lots of pimples if we leave grains of rice in our bowl; we were told that the grains of rice left were the amount of money we will lose; we were told that we will be poor if we do not finish our rice. Anything and everything to make sure we do not waste.

Since young, we were taught that any failure or shortcoming is due to our lack of industry and shrewdness, rather than the fate of the heavens. Historian David Arkush compared Russian proverbs to Chinese proverbs to show this cultural difference.

If there was a bad harvest, a typical Russian proverb would exclaim: “If God does not bring it, the earth will not give it” – a symbol of fatalism and pessimism. On the other hand, the Chinese would blame their bad harvest on their lack of hard work, shrewd planning, and self-reliance.

They would say: “If a man works hard, the land will not be lazy”; they would sing: “Farmers are busy; farmers are busy; if farmers weren’t busy, where would the grain to get through the winter come from?”; they would admonish: “Don’t depend on heaven for food, but on your own two hands carrying the load”; and they would conclude: “No one who can rise before dawn three hundred sixty days a year fails to make his family rich.”

They would say: “If a man works hard, the land will not be lazy”; they would sing: “Farmers are busy; farmers are busy; if farmers weren’t busy, where would the grain to get through the winter come from?”; they would admonish: “Don’t depend on heaven for food, but on your own two hands carrying the load”; and they would conclude: “No one who can rise before dawn three hundred sixty days a year fails to make his family rich.”

Such was the observed harsh values the Chinese lived by, such that author Carl Crow in “The Chinese Are Like That” said: “If it is true that the devil can only find work for idle hands, then China must be a place of very limited Satanic opportunities.”

Family must be protected from poverty

More importantly, the Chinese work hard for security and family.

Professor of anthropology Steve Harrell found that most Chinese, especially overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia, work hard not to maximise profits, but to establish hedges and defend against losses. Most overseas Chinese, as Robert Kuok noted, came from extreme poverty.

The humiliating memory of being looked down upon must never repeat. Jia, or the family, must be protected from poverty at all cost. And it is this familial concept that is central to why hard work is widely praised as a moral virtue.

The humiliating memory of being looked down upon must never repeat. Jia, or the family, must be protected from poverty at all cost. And it is this familial concept that is central to why hard work is widely praised as a moral virtue.

It echoes the Taoist ethic of selflessness – that individual ego is destructive – and the Confucian virtue of filial piety and lifelong duty to your family.

This article is, of course, not implying that other non-Chinese are not hard workers. It is to ask if there is truth to the stereotype.

In fact, the conclusion should give us some reassurance that hard work is universally attainable as a cultural value, since it is not something you are born with; instead, it is something you can learn and pass on to the next generation.

And that is surely one of the essences of being Chinese: to know that everything must be worked for, and nothing is a given.

JAMES CHAI works at a law firm. His voyage in life is made less lonely with a family of deep love, friends of good humour and teachers of selfless giving. This affirms his conviction in the common goodness of people: the better angels of our nature. He tweets at @JamesJSChai.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.