-K. Siladass, December 22, 2016.

am grateful to my friend Mr. K. Shanmuga for drawing my attention to the status of the national language version of the Federal Constitution. In my article, “The word ‘Parent’ in Article 12(4) of the Federal Constitution” which was published in the Online Malay Mail, and Bar Website on 5 December 2016, I stated that the national language version of the Federal Constitution is in force. It is not. The error is regretted.

am grateful to my friend Mr. K. Shanmuga for drawing my attention to the status of the national language version of the Federal Constitution. In my article, “The word ‘Parent’ in Article 12(4) of the Federal Constitution” which was published in the Online Malay Mail, and Bar Website on 5 December 2016, I stated that the national language version of the Federal Constitution is in force. It is not. The error is regretted.

For the sake of convenience, I reproduce Clause 160B which reads:

“160B. Where this Constitution has been translated into the national language, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong may prescribe such national language text to be authoritative, and thereafter if there is any conflict or discrepancy between such national language text and the English language text of this Constitution, the national language text shall prevail over the English language text.”

This amendment came into effect on 28 September 2001.

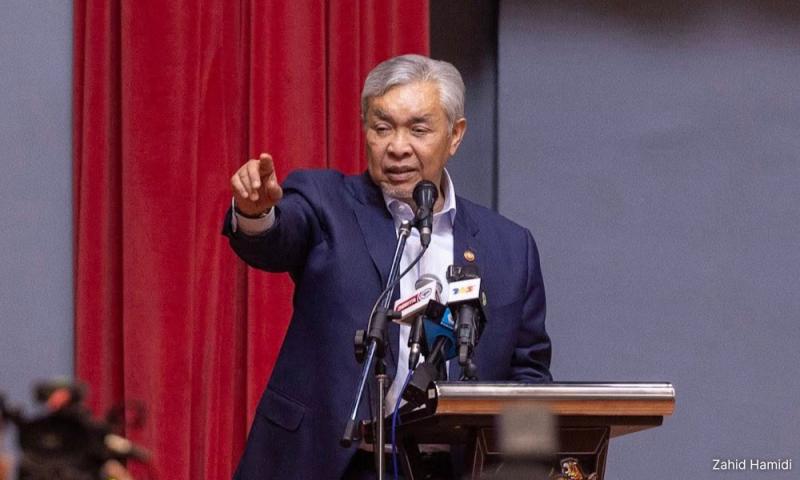

On September 30, 2003, The Star carried the story under the heading that the “Malay version of Federal Constitution launched”. The Star reported that the Yang di-Pertuan Agong has launched the Malay version of the Federal Constitution at a ceremony attended by, among others, the then Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Abdullah Badawi (now Tun Abdullah Badawi). It also stated that the Malay version of the Federal Constitution will supersede the English text as the authoritative Supreme law of the Country when it receives Royal Assent from the Yang di-Pertuan Agong.

So, what is the effect of Clause 160B? It requires the Yang di-Pertuan Agong to prescribe that the national language text to be authoritative when it is so translated. The Yang di-Pertuan Agong’s role is confined to prescribe such national language text to be authoritative. There is no evidence to show that the Yang di-Pertuan Agong has acted in accordance with Clause 160B. But, if we are looking at the words “where this Constitution has been translated into the national language…” and coupled with the fact that the Yang di-Pertuan Agong has launched the national language version, it could be argued that the first condition “where this Constitution has been translated into national language” has been satisfied; but, the second condition seems not to have been fulfilled even after fifteen years. However, the national language version is in circulation.

In Indira Gandhi a/p Mutho v Pengarah Jabatan Agama Islam Perak & Ors [2013] 5 MLJ at p. 572, Lee Swee Seng, then a Judicial Commissioner has stated: “If the framers had wanted the decision of a single parent to be all-sufficient in any and every situation, they could have used the expression ‘… decided by either of his parents …’ or ‘… decided by any one of his parents …’ or even ‘… decided by his father or mother…’ as is the current translation used in the Bahasa Malaysia translation done by the attorney general’s chambers. It seems that before 2002 the Bahasa Malaysia translation of the Constitution as printed by the government printers had used the words ‘ibu bapa’ instead of ‘ibu atau bapa’ in art 12(4). The translation of ‘parent’ into ‘ibu bapa’ is a direct translation whereas the translation ‘ibu atau bapa’ is an interpretative translation. The official version remains the English version under art 160A as the relevant prescription of the national language version under art 160B has not been effected. Learned senior federal counsel (‘SFC’) Encik Noorhisham has not submitted otherwise.” (emphasis is mine)

The national language version of the Federal Constitution is indeed very popular and is available in the market. It is being treated as the authoritative text notwithstanding the fact that the English version is still the authoritative text. The attitude to hold that the word “parent” means either the father or mother is consistent with the unauthoritative national language text but not the English text which is still the authoritative text.

It would be suggested that the national language version should be corrected to reflect, the true spirit, that is, both parents, father and mother, must consent to convert a child under the age of eighteen years before it is prescribed as the authoritative text. Otherwise it will defeat the objective of the current move in Parliament which aims to make it compulsory that both parents must consent to the conversion of a child under eighteen to Islam.

If Parliament were to amend Article 12(4) and make it clear that a person under the age of eighteen could only be converted with the consent of the father and mother or guardian much of the confusion that had hitherto generated could be avoided.