Conflicting views have emerged following the announcement by Datuk Seri Takiyuddin Hassan, the Law Minister in Prime Minister’s Department that the Federal government has revoked the Emergency Ordinances. It will be recalled that when Takiyuddin made the announcement in Parliament when it resumed sitting on 26th July 2021, members did point out that copies of the Ordinances had been placed on their tables implying that they are laid before both Houses of Parliament for debate. When members of the House questioned Takiyuddin as to when the Emergency Ordinances were revoked, he answered that it was done on Wednesday the 21st July 2021, the Cabinet meeting day.

When we look at the constitutional provisions it can be seen there are procedures to be followed in relation to the revocation of Emergency Ordinances. Takiyuddin did not elaborate whether the constitutional requirements had been complied with, especially whether the Yang di-Pertuan Agong had consented to the revocation.

Leaving aside, for the time being, the question whether His Majesty the Yang di-Pertuan Agong’s consent was obtained, the country is entitled to know:

- i) what impeded the government from making it public before 26th July 2021 that the Emergency Ordinances had been revoked as stated by Takiyuddin?

- ii) If it is true that the Emergency Ordinances had been revoked on 21st July 2021, then, what was the necessity of laying them on members’ tables implying debate on them?

Coming to the issue of revocation of the Proclamation of Emergency and the Ordinances promulgated during Emergency proclaimed under Article 150 of the Federal Constitution the procedure for revocation or the cessation of their effectiveness are spelt out in Article 150 (3) and (7) of the Federal Constitution, and they are:

- i) Under Article 150(3), the moment Parliament resumes sitting the Proclamation of Emergency and any Ordinance promulgated by the Agong shall be laid before both Houses of Parliament, if they had not been revoked earlier, and they shall cease to have effect if both Houses pass a resolution annulling the Proclamation and the Ordinances, or

- ii) Under Article 150 (7) on the expiration of a period of six months beginning with the date of Proclamation of Emergency and any Ordinance promulgated will cease to have effect with saving provisions for things done or for omissions.

There are clear authoritative judicial precedents which say that any revocation of the Proclamation of Emergency and Ordinances promulgated when the emergency was in force could only be done by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong on the advice of the Cabinet. Support for this proposition could be gleaned from the Privy Council case of Teh Cheng Poh against Public Prosecutor (1979) Malayan Law Journal, volume one at page 53 where Lord Diplock in his speech stated that the “power to revoke, however, like the power to issue a proclamation of emergency vests in the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, and the constitution does not require it to be exercised by any formal instrument.” It is, therefore, obvious that only His Majesty could revoke Emergency Ordinances on the advice of the Cabinet. Assuming, as in the present situation, if His Majesty were to withhold consent to revoke the Proclamation of Emergency and the Ordinances promulgated, can the Government itself revoke them? The government has no such power, and to do so will be akin to usurping the functions of His Majesty. That would be patently unconstitutional, and a result unenvisaged by the framers of the Constitution.

Now the question arises whether His Majesty has indeed consented before 26th July 2021 to the revocation of the Proclamation of Emergency and the Ordinances promulgated during the emergency, or put it neatly, revoke them before Parliament sitting began?

His Majesty’s Office has in no uncertain terms stated that:

- His Majesty did not consent to the revocation of the emergency Ordinances;

- His Majesty wanted the Ordinances to be laid before Parliament and insisted that Parliament should debate on them.

It must be added that the Yang di-Pertuan Agong is not prevented from seeking clarification or suggest changes on the advice so given by the Cabinet.

In response to His Majesty’s categorical denial of consent the Prime Minister says that the revocation was done according to law. Events as presented for public consumption show otherwise.

Thus, what actually happened has been made public and it would seem that the Federal Government has acted in haste and unconstitutionally.

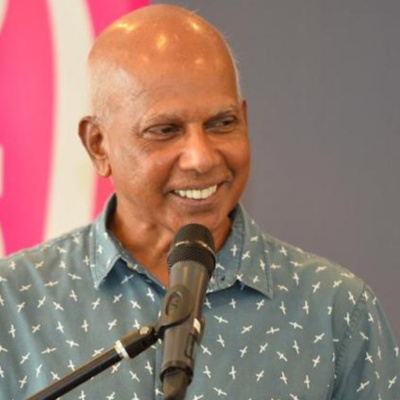

In the midst of the conflicting versions from the Istana Negara and Putrajaya, Datuk Seri Gopal Sri Ram, an eminent jurist, is reported to have expressed the view that His Majesty’s signature is not essential to revoke the Ordinances.

Sri Ram’s view invites consideration of various factors. If we take it at face value it seems to suggest that His Majesty could simply signify consent by mere signs and that should suffice. A sort of Homer’s nod. This view, it is submitted, will open up for the proliferation of unimaginable unsavoury acts, and it could be safely said that the framers of the Constitution did not envisage such a course e.g., His Majesty’s signature is not essential to revoke the Ordinances. Such a course could lead to endless friction between the Palace and Putrajaya. On the question of consent Sri Ram says that there is judicial precedence and refers to the case of Government of Kelantan against Government of the Federation of Malaya (1963), Malayan Law Journal, page 355.

The facts of the Kelantan case revolved around the formation of Malaysia. The Kelantan Government sought a declaration that the Malaysia Agreement and the subsequent Malaysia Act 1963 are null and void. The Kelantan government’s grievances could be summarised as follows:

- the Malaysia Act in effect abolishes the Federation of Malaya and this is contrary to the 1957 Agreement;

- the proposed change requires the consent of each of the constituent State and this has not been obtained;

- the Ruler of Kelantan should have been a party to the Malaysia Agreement, which was not the case;

- constitutional convention requires that the Rulers of the individual States should be consulted regarding substantial changes in the constitution;

- in any event the Federal Parliament has no power to legislate for the State of Kelantan.

Going through the case it could be gathered that the main issue there was whether the Federal Government had the capacity and competence to establish Malaysia with three new States i.e., Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak. Chief Justice Thompson who heard the matter pointed out that Parliament has the power to admit new territories into the Federation, under Article 2 of the Federal Constitution. In other words, Parliament has the exclusive power to admit new territories, as such the consent of the constituent states or the Rulers was not necessary. Kelantan Government’s attempts to abort the birth of Malaysia on 16th September 1963 was judicially thwarted.

Another argument that has been advanced in support of the Government’s stand in relation to revocation of the emergency Ordinances is that there is no provision in the constitution requiring His Majesty’s consent. The Constitution does not say, particularly in cases of revocation of Emergency Ordinances that the government could revoke them. What is good for the goose is good for the gander.

Reverting to the present crisis, the Emergency Ordinances proclaimed by His Majesty on the advice of the Cabinet can only be revoked by the same process when Parliament is suspended. It could be said that when Parliament remains suspended the role of the Agong is manifold in the sense he is the guardian of the constitution. He assumes the role of Parliament i.e., the role of the people’s representatives. It could therefore be correct to say that the Agong has the right to check accuracy and practicality of any advice given by the Cabinet. It should be perfectly in order to say that when Parliament is suspended His Majesty is the parliament.

Going by this reasoning it is submitted that the Emergency Proclamation and the Ordinances proclaimed and promulgated respectively on the advice of the Cabinet can only be revoked by the same process when Parliament is not sitting.

As it is, after weighing all the facts that are put before the public there is strong ground to conclude that the Proclamation of Emergency and the Ordinances promulgated during the emergency have not been constitutionally revoked.

Constitutional wisdom calls for the correction of a wrong, which if left unattended will give rise to other unimaginable violations in the name of precedence.

By the time this article was concluded, there was news that the government has agreed to table the Ordinances at the next Parliament sitting. A wise move.