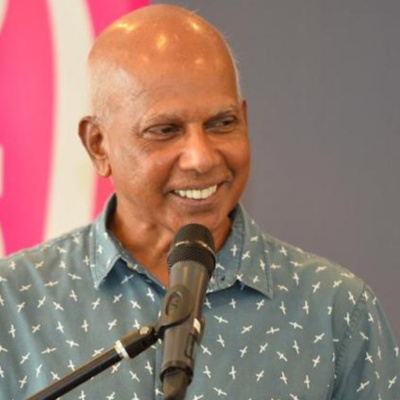

Malaysia can indeed leave the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPPA) if it chose to do so, said economist Jomo Kwame Sundaram.

Malaysia can indeed leave the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPPA) if it chose to do so, said economist Jomo Kwame Sundaram.

However, this will not be without cost to Malaysia, as it would still have to honour commitments made while the agreement was still in effect, even after leaving.

He said this in a public lecture at the University of Malaya today, when asked if there was any truth to International Trade and Industry Minister Mustapa Mohamed’s claim that Malaysia can exit the TPPA at any time.

“Tok Pa is correct. You can leave, but not without cost […]. Let’s just say that right now, we start in 2018; we join for one year and at the end of 2018, the next government decides to pull out.

“But all the commitments made have to be respected – we are liable to those commitments,” he said.

He explained that India is also facing a similar predicament, after giving notice that it intends to withdraw from bilateral investment treaties (BIT) it had signed.

The decision came after an investor-state dispute initiated under one of its BITs was decided against the Indian government, in contradiction to an Indian Supreme Court ruling.

“After giving notice, those commitments which were made, and those investments which were made because of the existence of the BIT; you cannot just say ‘Oh sorry, I am no longer a signatory to the BIT’. So it is not completely costless, but he is right that we can opt out,” he said.

Controversial provisions

BITs, in general are analogous to TPPA’s investment chapter, and both contain controversial provisions that allow foreign investors to sue governments if their investments are expropriated, or if a policy change would result in a loss of profits.

TPPA’s proponents argue its investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) provisions contain stronger safeguards that give governments more powers to enact policies in the public interest; detractors argue that these provisions are inadequate, and alternative avenues for settling investment disputes are not explored.

Malaysia signed the TPPA in February this year, and has two years to ratify it.

The agreement allows signatories to pull out from the agreement upon giving six-months’ notice.

Conflicts of interest

On a related matter, Jomo said many people believe that the US has never lost a suit because of conflicts of interest inherent in the system.

The three-member panel presiding over such suits come from a small community of less than 200 lawyers, who may be litigating in other suits.

One member would have been picked by the investor, and another by the government being sued. A third member would have to be agreed upon by both parties.

If an arbitrator develops a reputation for being harsh against corporations however, corporations would never consent to having him or her as a third panellist, or approach him or her for their own cases.

He pointed out that US government had already resorted to similar tactics with the World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) arbitration panel.

The WTO system is separate from ISDS and arbitrates trade disputes between member states, rather than dealing with private investors.

He said the US had blocked the re-nomination of a South Korean judge who had previously decided against the US in such disputes.

“This is the way it works, but you need to have a have a lot of capacity to know who’s who, in order to work the system […].

“Basically, many people think that the reason why the US never loses a suit is because everybody knows that once the US loses, it will put an end to all this, just as they had put an end to Korean judge’s career,” he alleged, This, he added, allowed the US to win even when its case appeared very weak.

He added that the US Congress would likely ratify the TPPA, even though both its Democrat and Republican presidential candidates had voiced out against it.

This is because the US political system is highly corrupt, he said, and those who had been voted into office would have to return the favour to their campaign funders, which were often large US corporations.

Meanwhile, on a global scale, Jomo who was a former UN assistant secretary-general for economic development, said regional trade agreements including the TPPA, undermines the WTO’s multilateral trade arrangements.

This in turn jeopardised Malaysia’s and other developing countries’ abilities to negotiate for better deals through the WTO, compared to what was possible under regional trade agreements.